image: megacities.jpl.nasa.gov

Megacities Carbon Project

by Tim Willmott : Comments Off on Megacities Carbon Project

While national and international Climate Change policies are mired in a bog of ideological obfuscation, cities all around the world have quietly been getting on with things. In the UK, Bristol is the European Green Capital for 2015 and is busy developing policies and projects which will be accessible to other city-regions around the world. Some cities are already acknowledged trailblazers: Curitiba in Brasil; Hamburg, home to HafenCity; Masdar in Abu Dhabi; Kalundborg in Denmark and many, many more.

Step forward Riley Duren, an engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He and colleagues have spent the past four years working on the problem of accurately measuring and monitoring greenhouse gas emissions from large cities.

This year, using one of the most complex cities in the world, they hope to prove they have a solution.

“It turns out that about three-quarters of fossil fuel CO2 emissions come from about 2 percent of the land surface. It’s the cities, and it’s the power plants that feed the cities,” Duren said.

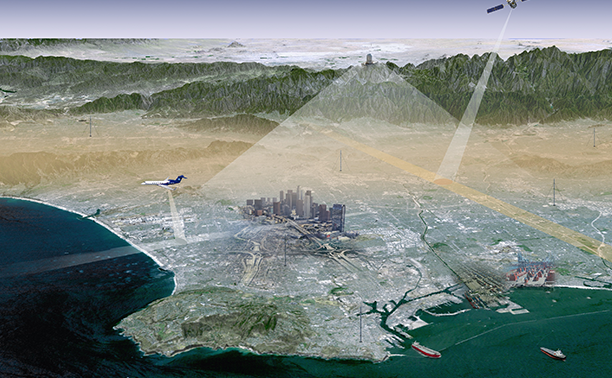

Duren coordinates an effort called the Megacities Carbon Project. Its goal: to accurately monitor cities’ greenhouse gas emissions using both surface-based and satellite monitoring systems, as well as the most advanced bottom-up estimates of city emissions.

He and his fellow researchers believe that cities, and their emissions patterns, likely fall into a typology. Such a categorization would be based on socioeconomics, topography, ecosystem types, meteorological conditions, available technology, and urban form.

One type might be the high-tech city whose emissions come primarily from transportation within its boundaries, another a middle-income city whose emissions are dominated by, say, coal-fired power generation.

“By instrumenting a subset of the cities and power plants with surface measurements, you can develop a model of how things work,” Duren said. “You can also use this to calibrate the other observing systems, such as satellites and aircraft.”

One day, Duren hopes, the combination of these two approaches will allow accurate monitoring of urban greenhouse gas emissions from space. The project also aims to help cities know whether their attempts to reduce emissions are working — and if not, show where they need to focus additional reduction efforts.

To test this concept, Duren and his colleagues have decided to try their network of instruments and models out in a large, complex city: Los Angeles.

Instrumenting a city

Instruments, television antennas and an astronomical observatory dot the top of Mount Wilson, a 5,700-foot peak in Los Angeles’s San Gabriel Mountains.

Some of these instruments are part of the megacities project. One of them looks across the L.A. basin, using reflected sunlight to measure the column of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Satellites measuring greenhouse gases essentially do this, but by looking downward.

Other instruments, some mounted on mounted on radio towers and rooftops in a dozen or so strategic locations around the city, are sniffing the city’s air, measuring concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and carbon monoxide.

The ideal greenhouse gas monitoring station is a tall radio tower, Duren said. A shed at the base holds instruments that measure concentrations of greenhouse gases. From there, an intake tube runs hundreds of feet into the sky, sharing space with the tower’s antenna. Pumps pull in the air and suck it down to the instruments, which measure greenhouse gases and transmit those measurements out to servers.

Right now, the Los Angeles team is making sure the network is taking accurate measurements — that the amount of CO2 and methane the instruments say they are measuring is what they are actually measuring. In early 2015, they hope to make the data available to other researchers and, eventually, the public.

Duren is coordinating with other groups that are instrumenting additional megacities. There’s a similar effort in Paris, and the group also hopes to measure emissions in a tropical city, perhaps São Paolo, Brazil, whose mayor has also committed to greenhouse gas reductions.

“If a city is meeting its policy targets, then we should be able to see the emissions going down — and maybe help link those trends to major sectors or actions,” Duren said.

A ‘map’ of emissions

Kevin Gurney, a climate scientist at Arizona State University, is working on another part of the megacity problem.

While atmospheric measurements will help policymakers understand whether emissions are going up or down, and how various sectors of a city contribute to emissions, Gurney’s goal is to provide a lot more detail about the specific sources of those emissions.

The result is a kind of map of emissions that will help policymakers know what is causing them and where they are coming from, he said.

“At the end of the day, we are trying to figure out the when and where of the emissions, what is coming out of the city — out of the tailpipes of cars, the stacks of power plants, people’s houses. We want to be able to estimate it all,” Gurney said.

If he finds a whole lot of emissions are coming from local commercial transport, say, that could give the city a policy goal of improving gas mileage on those vehicles. If buildings are a big source, perhaps the city could encourage insulation.

“It used to be, just broadly speaking, ‘How can we reduce emissions?’ And nowadays it’s like, OK, now that we are actually going to spend money, [the city wants] to know, ‘Where?'” Gurney said.

It’s not an easy task to identify the precise sources of greenhouse gases in a city. After all, cars don’t have CO2 monitors on their tailpipes, and houses and buildings don’t record how much they emit, either.

To tally up greenhouse gas sources from a city, Gurney gathers as much data as possible about such things as building types and occupancy schedules, traffic patterns, the mix of diesel and light trucks on the road.

He compiles all that information and basically adds it up as a way to estimate just how much greenhouse gases different sources are releasing. This technique is called a bottom-up estimate.

If Gurney had perfect information about all these processes, this would be a great way to understand total emissions and the amounts from each source. But since there are a lot of assumptions involved and the data come from a range of sources, there can significant uncertainty in a bottom-up estimate.

In Los Angeles, one goal of the Megacities Project is to match that bottom-up approach with the measurements of emissions coming from the atmospheric sensors and the models used by the project. The atmospheric approach also has uncertainties, but when put together, they overcome each other’s weaknesses.

“It’s the merger of these two [approaches] that is very powerful,” Gurney said. “And if we can do it in L.A., we can probably do it almost anywhere.”

Targets for policymakers

As more and more cities make serious commitments to reducing emissions, James Whetstone, a scientist at the National Institutes of Standards and Technology who has been involved in the Megacities Project and another effort to quantify emissions in Indianapolis, says projects like this one, which will reduce the uncertainty associated with city-level emissions, will become increasingly necessary.

“If you’re on the hook for demonstrating that you are either going toward a target or that you’ve met a target, as time goes by I think you’re going to have to have credible measurement results in order to do that,” Whetstone said.

Once the Megacities data are up and running, those involved want to publicize the greenhouse gas measurements so city residents can track the progress of their city.

“Our vision, if this becomes a global monitoring system, then you get more accurate, transparent assessments of scrutiny of claimed emissions reductions,” Duren said.

Ideally, greenhouse gas emissions might be reported on the nightly news or alongside weather outlooks, said Molly Macauley, an economist and senior fellow at Resources for the Future. The idea is, if city residents can see how well their municipality is doing on meeting its greenhouse gas targets, they might want to become more involved in reducing those emissions.

“There’s a large economic literature that says if citizens can see a benchmark of their progress, then it increase compliance,” Macauley said.

If the Megacities team’s vision comes true, perhaps just a few years in the future, a network of surface stations and monitoring satellites will allow any city resident to open up his smartphone, and along with checking the news and Facebook, he’ll also be able to check in with his city’s progress on greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

“The analogy here is kind of like the Weather Service, but for carbon,” Duren said. “At some point, this will become mundane, and people will just take it for granted. This will just always be running in the background.”

source: © eenews.net

Comments are closed