image: Miguel Ortega Lafuente

fukushima revisited: nuclear accidents

by Tim Willmott : Comments Off on fukushima revisited: nuclear accidents

I remember that carbon wizard Anthony Turner, who runs Carbon Sense, once told me that the atmosphere has no political boundaries. And just as carbon dioxide affects everyone, so too does nuclear pollution. It all depends on air (and sea) currents. And I suppose a major reason why nuclear bothers people so is that it is one hundred percent man-made. Earthquakes and tsunamis are aptly named ‘acts of God’. Nuclear accidents are not, cannot be. Yes, it’s a bit silly to build a nuclear power plant on a fault line, but you can’t blame the accident on the earthquake.

I’m not going to quantify the ridiculously dangerous stuff that is released in nuclear accidents, nor go into half-lives of isotopes, but I think it is necessary to know what happens. It’s not pleasant, so watch it only if you must:

Nuclear Accidents

There have been four significant accidents at nuclear power plants:

- Windscale in Cumbria, UK;

- Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania, USA;

- Chernobyl, Russia;

- Fukushima Daiichi, Japan.

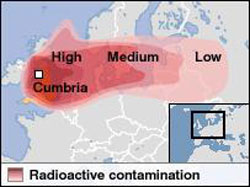

Windscale

On October 10, 1957 the graphite core of a British nuclear reactor at Windscale Cumbria, caught fire, releasing substantial amounts of radioactive material. The Windscale site was home to Britain’s first two nuclear reactors – the Windscale Piles – which were constructed to produce plutonium and other materials for the UK’s nuclear weapons programme

On October 10, 1957 the graphite core of a British nuclear reactor at Windscale Cumbria, caught fire, releasing substantial amounts of radioactive material. The Windscale site was home to Britain’s first two nuclear reactors – the Windscale Piles – which were constructed to produce plutonium and other materials for the UK’s nuclear weapons programme

At its peak, 11 tonnes of uranium were ablaze. The fire itself released an estimated 20,000 curies (700 terabecquerels) of radioactive material into the nearby countryside, although recent reworking of contamination data has shown national and international contamination to have been much higher than previously estimated.

The reactor was unsalvageable. Where possible, the fuel rods were removed, and the reactor bio shield was sealed and left intact. Approximately 6,700 fire-damaged fuel elements and 1,700 fire-damaged isotope canisters remain in the pile. Windscale Pile no. 2, though undamaged by the fire, was considered too unsafe for continued use. It was shut down shortly afterward

In the aftermath of the accident, the true scale of the event was concealed from the public, and the majority of the blame was apportioned to the plant operators. For 50 years, the official record on the accident has been that the very men who had averted a potentially devastating accident were to blame for causing it.

Three Mile Island

The Three Mile Island accident was a partial core meltdown in Unit 2 (a pressurized water reactor) of the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania near Harrisburg,United States in 1979.

The Three Mile Island accident was a partial core meltdown in Unit 2 (a pressurized water reactor) of the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania near Harrisburg,United States in 1979.

The accident began at 4 a.m. on Wednesday, March 28, 1979, with failures in the non-nuclear secondary system, followed by a stuck-open pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) in the primary system, which allowed large amounts of nuclear reactor coolant to escape. The mechanical failures were compounded by the initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation as a loss-of-coolant accident due to inadequate training and human factors, such as human-computer interaction design. In particular, a hidden indicator light led to an operator manually overriding the automatic emergency cooling system of the reactor because the operator mistakenly believed that there was too much coolant water.

In the three decades since Three Mile Island, the plant has become a rallying symbol for the anti-nuclear movement. But the nuclear power industry, which has not built a single new plant in the United States since 1979, says the accident showed that its safety systems worked, even in the most extreme circumstances.

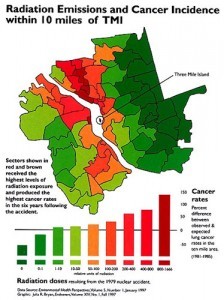

Revelations during the decade-long clean-up of the crippled reactor showed that its core was more seriously damaged than originally suspected. But scientists still disagree on whether the radiation vented during the event was enough to affect the health of those who lived near the plant.

Cleanup of the crippled reactor took more than 10 years, and assessments of health consequences have varied over time. In 1990 a major independent review led by a Columbia University epidemiologist found no evidence that radioactivity released during the accident caused any increase in cancer incidence during the six-year period immediately afterward.

Then in 1997 a report by researchers at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill concluded that increases in lung cancer and leukemia near the Three Mile Island nuclear plant suggested a much greater release of radiation during the 1979 accident than had been believed.

Chernobyl

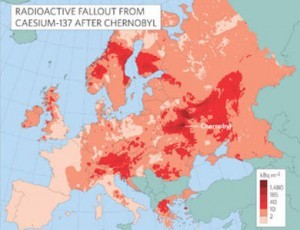

The Chernobyl disaster triggered the release of substantial amounts of radiation into the atmosphere in the form of both particulate and gaseous radioisotopes. It is the most significant unintentional release of radiation into the environment to date.

The Chernobyl disaster triggered the release of substantial amounts of radiation into the atmosphere in the form of both particulate and gaseous radioisotopes. It is the most significant unintentional release of radiation into the environment to date.

The explosion at the power station and subsequent fires inside the remains of the reactor provoked a radioactive cloud which drifted not only over Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, but also over the European part of Turkey, Greece, Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, Estonia, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, Ireland, France (including Corsica), Canada and the United Kingdom (UK). In France, the government claimed that the radioactive cloud had stopped at the Italian border.

The activities undertaken by Belarus and Ukraine in response to the disaster — remediation of the environment, evacuation and resettlement, development of uncontaminated food sources and food distribution channels, and public health measures — have overburdened the governments of those countries.

In September 2005, a comprehensive report titled “Chernobyl’s legacy: Health, Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts” was published by the Chernobyl Forum, comprising a number of agencies including the International Atomic Energy Agency(IAEA), the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations bodies and the Governments of Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine. The report put the total predicted number of deaths due to the disaster around 4,000. This number was subsequently updated to 9000 excess cancer deaths.

Chernobyl: Consequences of the Catastrophe for People and the Environment is an English translation of the 2007 Russian publication Chernobyl. It presents an analysis of scientific literature and concludes that medical records between 1986, the year of the accident, and 2004 reflect 985,000 deaths as a result of the radioactivity released. The authors suggest that most of the deaths were in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, but others were spread through the many other countries the radiation from Chernobyl struck. The literature analysis draws on over 1,000 published titles and over 5,000 internet and printed publications discussing the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster. The authors contend that those publications and papers were written by leading Eastern European authorities and have largely been downplayed or ignored by the IAEA and UNSCEAR.

Fukushima

The Fukushima accident has been progressively upgraded and is now a category 7 accident, up there with Chernobyl. There is a 30 kilometre exclusion zone around Fukushima, and this will remain now for the next 10,000 years. All that can happen now at the site is remedial work designed close down the reactors and to seal plant and secure the site.

How Safe Is Nuclear?

The World Nuclear Association (WNA) says that “It has long been asserted that nuclear reactor accidents are the epitome of low-probability but high-consequence risks. Understandably, with this in mind, some people were disinclined to accept the risk, however low the probability. However, the physics and chemistry of a reactor core, coupled with but not wholly depending on the engineering, mean that the consequences of an accident are likely in fact be much less severe than those from other industrial and energy sources. Experience, including Fukushima, bears this out.”

The World Nuclear Association (WNA) says that “It has long been asserted that nuclear reactor accidents are the epitome of low-probability but high-consequence risks. Understandably, with this in mind, some people were disinclined to accept the risk, however low the probability. However, the physics and chemistry of a reactor core, coupled with but not wholly depending on the engineering, mean that the consequences of an accident are likely in fact be much less severe than those from other industrial and energy sources. Experience, including Fukushima, bears this out.”

Unquestionably, Chernobyl has forced improvements in the design and management systems of nuclear power plant. WNA asserts “This once and for all vindicated the desirability of designing with inherent safety supplemented by robust secondary safety provisions and avoiding that kind of reactor design.” However, such a statement begs the question: Why was this ever not the case?

It goes on to say that “The use of nuclear energy for electricity generation can be considered extremely safe. Every year several thousand people die in coal mines to provide this widely used fuel for electricity. There are also significant health and environmental effects arising from fossil fuel use.”

This is not an easy debate. Many of the arguments, for and against, are moral ones. Those who argue the case against nuclear think there is no economic case for its adoption, and this alone makes all of the ethical issues irrelevant.

In the first of these articles I looked at the scientific rationale behind nuclear energy.

In the next article I will look at the arguments for and against.

References

Windscale: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7030281.stm

Three Mile Island: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/tmi/tmi.htm and

http://medlibrary.org/medwiki/Three_Mile_Island_accident

Chernobyl: http://medlibrary.org/medwiki/Chernobyl_disaster_effects

World Nuclear Association: http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf06.html

Comments are closed