forest gardens

by Tim Willmott : Comments Off on forest gardens

Traditional agriculture systems controlled pests through diversification, planting a mixture of crops rather than the intensive monocultures of the modern agri-business. Companion planting, or ‘intercropping’ a variety of species, not only maintains biodiversity but has multiple systemic benefits:

- mixed farming helps protect against pests by promoting a dynamic balance between insects and their predators

- makes use of synergistic properties like deep rooted crops which bring water and nutrients up from below

- modifies micro-climate conditions like humidity, light, temperature and air movement

- encourages cross-pollination between species and preserves genetic diversity.

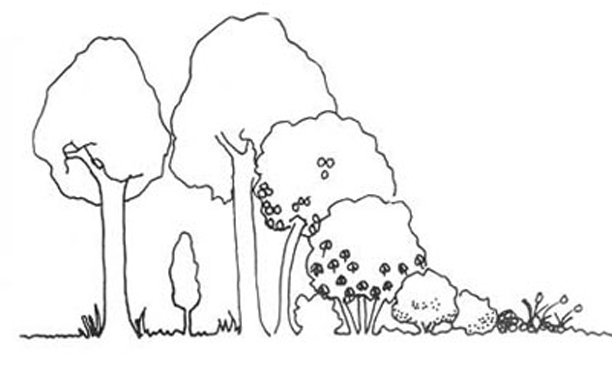

The forest garden concept has been well established in various parts of the globe. Some anthropologists believe that the complexity seen in parts of the Amazonian rainforest arose through human agro-forestry techniques and there are numerous examples of the high productivity that can be achieved through these methods. Rather than felling the existing trees, the Chagga settlers on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro planted bananas, fruit trees and vegetables in their shade. Now the individual plots, which average 0.68 hectares in size and contain some 17 vertical layers of vegetation, provide the entire subsistence for a family of ten people.

The most densely populated area in India, Kerala contains some 3.5 million forest gardens. These diversified and sustainable agro-ecological farming systems can generate astounding yields and provide employment and materials for a variety of industries. One plot of just 0.12 hectares for example, has been known to contain 23 coconut palms, 12 cloves, 56 bananas and 49 pineapples, with 30 pepper vines trained up the trees.

Associated industries in the area include the production of rubber, matches, cashews, furniture, pandanus mats, baskets, bullock-carts and catamarans, along with the processing of palm oil, cocoa and coir fibres from coconuts. Many families meet their own energy requirements through biomass systems fed by human, animal and vegetable waste, while the forest gardens provide full-time occupations for families which average seven members.

Kerala contradicts many of the current assumptions made about ‘wealth’, ‘quality of life’ and ‘standard of living’, much of which may derive from the abundance and nutritional value of these agricultural systems:

- Despite having an average annual income of around $350 – some 70 times less than his American equivalent – the life expectancy for a Keralite male is only two years less

- Kerala’s birth rate is falling from 18 per thousand to come in line with the US figure of 16 per thousand

- As well as providing a model of efficient and sustainable agriculture, producing more than any other Indian state, Kerala is now considered 100% literate, the same as the US and western Europe

- According to the Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI), Kerala rates higher than any other Asian country except Japan, despite being one of the most densely populated places on earth.

Comments are closed